Most of us recognize that excess stress is bad for our health and body composition, but not many of us understand why. Because if we did, we’d probably start paying a little more attention to the techniques for reducing it – instead of treating it like hippy mumbo-jumbo or a curfew from Mom and Dad, and purposely burning the candle at both ends in spite of it.

Well maybe not purposely, but the North American population is more stressed than ever. And not surprisingly, we’re seeing a steady decline in health and increase in degenerative disease as a result.

Obviously there’s more at play here (than just stress), and I’ll be the first to tell you it’s largely diet related. But the impact of stress can’t be ignored. Especially when we know it’s directly related to controllable behaviors – like how much we work, how much we rest, and how much we play.

Understanding Stress

Without going into too much detail, the stress response is a primal instinct designed to increase our chances of survival. Our blood pressure increases, energy floods to our muscles and brain, and we’re ready to think, move, and react quickly.

This ‘fight or flight’ process, coined ‘the alarm reaction phase’ by the great Hans Selye, involves the adrena medulla (found in the adrenal glands) releasing a massive amount of hormones (called catecholamines) after getting a direct message from the brain (the two are directly connected) that somethin’ smells fishy. This is followed closely by the adrenal cortex (also found in the adrenal glands) releasing steroid hormones (corticoids), which help increase blood flow and blood sugar.

The problem is, we’re biologically designed to follow up this ‘sympathetic’ response with a ‘parasympathetic’ reaction shortly after – where the adrenal glands stop secreting extra hormones (adrenaline, aldosterone, cortisol), our kidney’s stop hanging onto water and salt, blood glucose returns to normal, and energy and resources are redistributed to non-urgent, non-life threatening systems that were sacrificed during the emergency (digestive, reproductive, immune).

Parasympathetic = Rest & Digest, Feed & Breed

Or put another way, stress is supposed to be acute not continuous, and occasional not consistent. And unfortunately, without regular recovery we get into Selye’s ‘resistance’ and ‘exhaustion’ phases, where excess glucocorticoids (like cortisol) and mineralocorticoids (like aldosterone), negatively affect our carbohydrate tolerance, nutrient metabolism, inflammatory balance, gut health and immune system (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8)

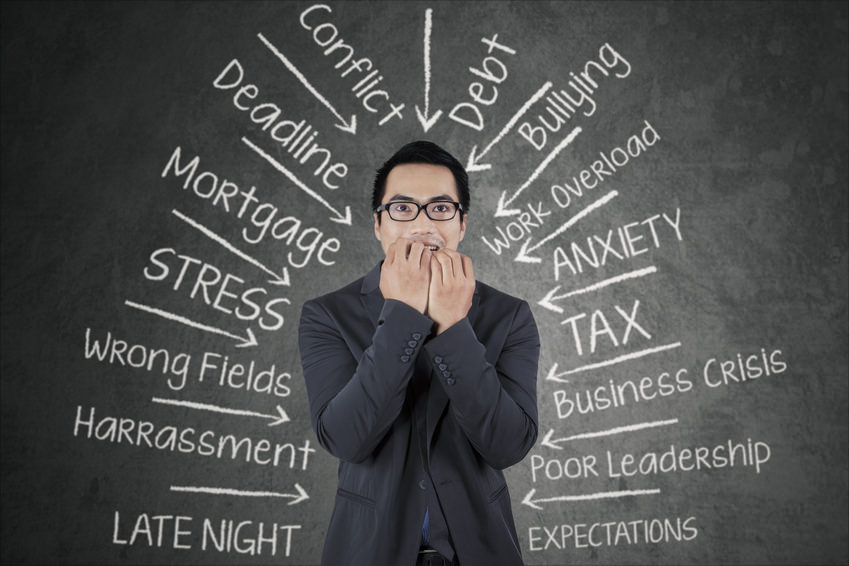

Basically, the over-stressed executive is fight-or-flight from the time they get up in the morning to the time they go to bed. Whether that’s thinking about what they have to do, doing what they have to do, worrying about what they just did, or stressing about tomorrow. Since the brain controls the response, and ‘perceived’ danger is equivalent to ‘actual’ danger.

Thus, without even getting into what Stock Brocker Sam is eating, if Stock Broker Sam is sleeping, and whether Stock Broker Sam is exercising, we know aldosterone, cortisol, and epinephrine are chronically pumping out of his adrenal glands, which elevates his heart rate, increases his blood sugar, and tells his digestion, reproductive hormones, and immune system to take a backseat.

And we wonder why high-stress people get sick?

Sadly, high-stress people also tend to carry excess body fat, and have trouble gaining and maintaining muscle mass too. Which isn’t surprising, given what we know about chronically elevated blood sugar and insulin, and given that chronically cortisol makes us store fat (specifically in the midsection), burn muscle, and lose our insulin sensitivity. Not to mention, being pre-cursors for the metabolic syndrome, and the diabetes and heart disease that comes after it.

But what’s worse, is that the systemic release of corticoids increases inflammation (1, 2, 3). Meaning circulating cytokines in our blood on a chronic and consistent basis, and an increased risk of the chronic inflammatory conditions that occur as a result.

- arthritis

- psoriasis

- asthma

- dementia

- atherosclerosis

- obesity

- diabetes

- depression

- cancer

- inflammatory bowel disease

- multiple sclerosis

- type 1 diabetes

The good new being, just like inflammation, stress can be controlled. And the better news being, you have more control over it than inflammation. Because aside from avoiding behavior’s that promote it (lack of sleep, worrying, etc) you have the ability to control your personal response to it (1, 2).

“Stress is not what happens to you, but how you react to it” – Hans Selye, Stress of My Life, 1977

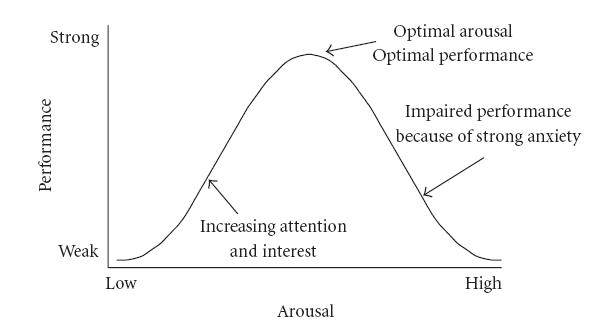

Moreover, acute stress applied to the right person at the right time, results in favorable adaptations (eustress) – with exercise being the perfect example.

In all cases, the key is striking a balance between your sympathetic (work) and parasympathetic (rest) nervous system – also referred to as your “allostatic balance.” Which ultimately comes down to controlling the cumulative total of anything and everything in your life that causes mental, physical and emotional stress (allostatic load).

In today’s world, this usually means increasing our parasympathetic time away from technology. Since being connected is stressful enough as it is, and worrying about the news or getting worked up on reality TV triggers the alarm phase we don’t want (especially in the evening). Getting longer, high-quality sleep should be priority #1; followed by exploring other ways to recharge your batteries (like meditation).

It also means turning distress (the bad stuff) into eustress (the good stuff), by doing your best to create a simple one-task, distraction-free environment. Because regardless of the size, task accomplishment builds self-efficacy (1, 2), while a giant list of half-completed To-Do items, or getting side-tracked by the ADHD that is the internet, promotes the opposite. So try warming with small tasks you can accomplish with ease, and work your way up from there.

Learning to say “no” and be selfish of your free time is also an extremely helpful practice. As if it’s not work or family related, and you’re not going to enjoy it, there should be no reason to do it – especially if it’s some one or some thing that adds distress.

Why sacrifice critical parasympathetic time that you need to stay balanced?

Lastly, it’s about matching the quantity of good stressors (eustress), like exercise, to your current allostatic load. Which could mean doing a little bit less (sets, weight, time), opting for a low-intensity stress-reducing activity (like walking) instead, or skipping the workout all together so you can get to bed early.

This may sound backwards for improving your health and body composition, but with the way people are operating these days it’s necessary. Chronic stress changes the way your body responds to meals, changes the way your body responds to exercise, and raises biomarkers for disease whether your regimen is perfect or not.

It’s also one of the hardest changes to make, because people who want to ‘do better’ have trouble doing what they perceive as ‘nothing’ to get there.

But it isn’t ‘nothing,’ because perfect balance is achieved by touching extremes at both ends (ex: acute stress with exercise, recovery with sleep), and doing your best to avoid living a life that’s dominated by one or the other (ex: high stress work, zero activity).

Not only so you can thrive and be happy, but because realistically your life depends on it.

Stay Lean!

Coach Mike

RELATED ARTICLES:

Walking is a Man's Best Medicine

Is Drinking Wine Part of a Healthy Diet?